No bomb that ever bursts shatters the crystal spirit:

With Farid and others in a British prison

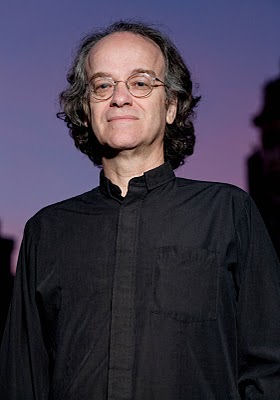

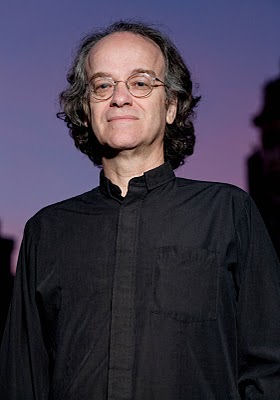

By Kevin Annett

I wear as a badge of honour my deportation

from a country of liars and cut throats.

- Big Bill Haywood, IWW leader and

revolutionary, 1920

The filthy fiction calling itself the

Crown of England finally vomited me from its midst this

week, only five days before I was to speak of its crimes

at the annual Against Child Abuse Rally in London's

Trafalgar Square.

I am proud to have shared a British

prison with many freedom fighters over time, including

my own ancestor Peter Annett; but also alongside

nameless men and women who are caught today in the claws

of the police state called Britain.

Here is what happened:

The room is small, unventilated, and

foul-smelling, and crammed with ten of us. I am the only

white person there.

A Malaysian mother with her four year old

daughter sits in one corner, sobbing uncontrollably.

Incarcerated for half a day, she’s one of the luckier

ones: a young Turkish man called Farid has languished in

here for nearly three days, isolated from his four

children. Farid has lived in England for eleven years,

doing sweat jobs and loyally paying his taxes, but

tomorrow he’ll be deported over a technicality in his

work visa.

There is no appeal allowed. His children

will not accompany him.

This is the Immigration Prison in

Stansted airport, outside London. The date is the early

hours of May 30, 2011.

The net fell on me suddenly the night

before, as I made my way through the border control desk

after disembarking from the Netherlands.

A banal little twit in a uniform scanned

my passport through his computer, and quickly looked

shocked as he peered through thick lenses at the screen.

He scuttled off to speak to his supervisor, who I

watched through the glass window of his office as he

looked at his own computer, nodded his head and said

something to the twit.

Triumphantly – I guess he got extra

points for bagging a suspected enemy of the state – Twit

boy returned and informed me with a whine of

condescension that my giving public lectures was

“unusual” for a tourist, that I was "suspect", and would

therefore be barred from entering England.

"What exactly am I suspected of doing?" I

asked the guy.

“But first you are to come this way” he

motioned, ignoring my question like I hadn't said

anything, and we walked to a tiny holding cell. The Twit

left me alone in there for a half hour, I guess to make

me sweat, but when he returned I was calmly whistling an

Irish melody that seemed to annoy him to no end.

“I bet you find your job difficult” I

ventured to the Twit as he fiddled with his papers.

Attempting a smile, he answered,

“No, actually one meets very fascinating

people in this line of work” he replied.

“People like you, then?” I said, but I

don’t think he got my joke.

The Twit refused to give me his name when

I asked, nor could I know the name of his supervisor. He

also wasn’t wearing a badge number, although later he

made a gaff when he donned another coat and I saw his

number: 6676.

“You’ll be in here tonight, until we can

send you back from whence you came” Twit informed me,

gesturing to a white door. He knocked, and a stern young

guy answered who wore a vest labeled Reliance: the

private company that profits off incarcerating people

all over England.

Despair gazed back at me from the sad

eyes of my fellow prisoners who lay or sat around the

room. A TV was blaring mindless crap at them so I walked

over and shut it off. The young Turkish guy, Farid,

looked surprised.

After my obligatory finger printing and

photographing – I asked the Reliance guy if I could have

a copy of the picture, since I looked pretty good, but

he said no – I was locked into the sparse room with

everyone, and told not to speak to any of them since

that was against the rules. I just smiled.

Most of the detainees didn’t want to

talk. It was nearly midnight by then, and like anyone,

they had adapted to their incarceration and were mired

in themselves. But Farid was too filled with grief about

being robbed of his children to settle into apathy.

“I will never see them again. They will

be put with other families and then anything can happen

to them. My youngest son is only a baby.”

I remembered reading the day before how

586 children placed in the foster care system in England

had somehow disappeared over the past year. Local child

welfare officials had given no explanation concerning

their fate.

Farid taught me some Turkish words that

night, starting with “I love you” – it sounded like

“selly sev yurum”. He laughed for the first time when he

commented how the phrase might come in handy if I ever

came to his country, but not if I said it to a man.

“That’s not what I hear” I replied, and

he laughed even harder.

We held back the demons together during

those slow and weary hours, as the others tried to

sleep, and didn’t, and the Malaysian woman sang to her

daughter while the Reliance thugs stared at us through a

thick pane of glass.

It ended for me at 6 am, when I was taken

to a plane that would fly me back to Eindhoven. I said

goodbye to Farid and wished him luck.

He took my hand and said “Allah”,

pressing his other hand against his chest, and then

pointing to my heart.

I recalled then the last words in George Orwell's book

Homage to Catalonia, in which he describes

briefly meeting an Italian militia man who like Orwell

was fighting Franco and his fascists during the Spanish

civil war. They couldn't speak one another's language,

but they shook hands and departed in different

directions for the front lines, and Orwell never saw the

Italian man again.

In memory to this unknown stranger who had briefly taken

his hand in comradeship, and who had probably died,

Orwell wrote a poem to him that concluded,

But the look I saw in your eyes, no power can

disinherit.

No bomb that ever burst shatters the crystal spirit.

The night after my deportation, I stood

in a crowd of singing and laughing revealers in a Dublin

pub, tasting my freedom like a soothing ale, and

thinking of where Farid might be. I never felt unfree in

jail; nor did anything there or in his own agony stop

Farid from laughing.

As someone commented to me today,

the more they repress us, the sharper and stronger we

get. I feel inwardly clarified after the ordeal, and

from the sounds of things, what happened to me is simply

boomeranging back on the British government and its

obvious and quite clumsy attempts to stop our Tribunal

this fall.

So be of good cheer, and let that

hope propel your body and your life to continue to

accompany your words. But never forget Farid, and his

children ... and that which is trying to jail all of us.

...............................................................................................................................

See the evidence of Genocide in Canada at

www.hiddennolonger.com and on the website of The

International Tribunal into Crimes of Church and State

at www.itccs.org.

Watch Kevin's award-winning documentary film UNREPENTANT

on his website

www.hiddenfromhistory.org

"True religion undefiled is this: To make restitution of

the earth which has been taken and held from the common

people by the power of Conquests, and so set the

oppressed free by placing all land in common." - Gerrard

Winstanley, 1650

"We will bring to light the hidden works of darkness and

drive falsity to the bottomless pit. For all doctrines

founded in fraud or nursed by fear shall be confounded

by Truth."

- Kevin's ancestor Peter Annett, writing in The Free

Inquirer, October 17, 1761, just before being imprisoned

by the English crown for "blasphemous libel"

"I gave Kevin Annett his Indian name, Eagle Strong

Voice, in 2004 when I adopted him into our Anishinabe

Nation. He carries that name proudly because he is doing

the job he was sent to do, to tell his people of their

wrongs. He speaks strongly and with truth. He speaks for

our stolen and murdered children. I ask everyone to

listen to him and welcome him."

Chief Louis Daniels - Whispers Wind

Elder, Turtle Clan, Anishinabe Nation, Winnipeg,

Manitoba |